Missouri Botanical Garden

Missouri Botanical Garden | |

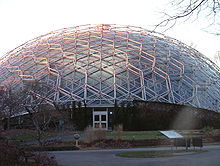

View of the Missouri Botanical Garden Climatron from the Central Axis area in 2023. | |

| Location | St. Louis, Missouri |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°36′45″N 90°15′35″W / 38.61250°N 90.25972°W |

| Built | 1859 |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian |

| Website | www |

| NRHP reference No. | 71001065[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 19, 1971 |

| Designated NHLD | December 8, 1976[2] |

The Missouri Botanical Garden is a botanical garden located at 4344 Shaw Boulevard in St. Louis, Missouri. It is also known informally as Shaw's Garden for founder and philanthropist Henry Shaw. Its herbarium, with more than 6.6 million specimens,[3] is the second largest in North America, behind that of the New York Botanical Garden. The Index Herbariorum code assigned to the herbarium is MO[4] and it is used when citing housed specimens.

History

[edit]The land that is currently the Missouri Botanical Garden was previously the land of businessman Henry Shaw.

Founded in 1859, the Missouri Botanical Garden is one of the oldest botanical institutions in the United States and a National Historic Landmark. It is also listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1983, the botanical garden was added as the fourth subdistrict of the Metropolitan Zoological Park and Museum District.

The garden is a center for botanical research and science education of international repute, as well as an oasis in the city of St. Louis, with 79 acres (32 ha) of horticultural display. It includes a 14-acre (5.7 ha) Japanese strolling garden named Seiwa-en; the Climatron geodesic dome conservatory; a children's garden, including a pioneer village; a playground; a fountain area and a water locking system, somewhat similar to the locking system at the Panama Canal; an Osage camp; and Henry Shaw's original 1850 estate home. It is adjacent to Tower Grove Park, another of Shaw's legacies.[5]

For part of 2006, the Missouri Botanical Garden featured "Glass in the Garden", with glass sculptures by Dale Chihuly placed throughout the garden. Four pieces were purchased to remain at the gardens. In 2008 sculptures of the French artist Niki de Saint Phalle were placed throughout the garden. In 2009, the 150th anniversary of the garden was celebrated, including a floral clock display.

After 40 years of service to the garden, Dr. Peter Raven retired from his presidential post on September 1, 2010. Dr. Peter Wyse Jackson replaced him as President.[6]

In 2024, the Tower Grove House was added to the Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. Records show that in 1855, four people enslaved by Shaw escaped the house and crossed the Mississippi River with help from Mary Meachum. A woman, Esther, and her three children were captured immediately after crossing. Shaw placed a bounty on Jim Kennerly, who had escaped.[7]

Leaders of the garden

[edit]- Henry Shaw (founder) until his death in 1889

- William Trelease, director, 1889 to 1912

- George Thomas Moore, director, 1912 to 1953

- Edgar Anderson, director, 1954 to 1957

- Frits Warmolt Went, director, 1958 to 1963

- David Gates, director, 1965 to 1971

- Peter H. Raven, director, 1971 to 2006; president and director, 2006 to 2010

- Peter Wyse Jackson, president, appointed 2010

- Lúcia G. Lohmann, president and director, starting January 2, 2025

Cultural festivals

[edit]The garden is a place for many annual cultural festivals, such as the Japanese Festival and the Chinese Culture Days by the St. Louis Chinese Culture Days Committee.[8] During this time, there are showcases of the culture's botanics as well as cultural arts, crafts, music and food. The Japanese Festival features sumo wrestling, taiko drumming, koma-mawashi top spinning, and kimono fashion shows. The garden is known for its bonsai growing, which can be seen all year round but is highlighted during the multiple Asian festivals.

Gardens

[edit]Major garden features include:

- Tower Grove House (1849) and Herb Garden – Shaw's Victorian country house, designed by prominent local architect George I. Barnett in the Italianate style

- Victory of Science over Ignorance – marble statue by Carlo Nicoli, a copy of the original (1859) by Vincenzo Consani in the Pitti Palace, Florence

- Linnean House (1882) – reputedly the oldest continually operated greenhouse west of the Mississippi River; originally Shaw's orangery, in the late 1930s converted to house mostly camellias

- Gladney Rose Garden (1915) – circular rose garden with arbors

- Climatron (1960) and Reflecting Pools – world's first geodesic dome greenhouse, designed by architect and engineer Thomas C. Howard of Synergetics, Inc; lowland rain forest with approximately 1500 plants

- English Woodland Garden (1976) – aconite, azaleas, bluebells, dogwoods, hosta, trillium, and others beneath the tree canopy

- Seiwa-en Japanese Garden (1977) – 14-acre (5.7 ha) chisen kaiyu-shiki (wet strolling garden) with lawns and path set around a 4-acre (1.6 ha) central lake, designed by Koichi Kawana; the largest Japanese Garden in North America

- Grigg Nanjing Friendship Chinese Garden (1995) – designed by architect Yong Pan; features (gifts from sister city Nanjing) a moon gate, lotus gate, pavilion, and Chinese scholar's rocks from Lake Tai

- Blanke Boxwood Garden (1996) – walled parterre with a fine boxwood collection

- Strassenfest German Garden (2000) – flora native to Germany and Central Europe and a bust of botanist and Henry Shaw's scientific advisor George Engelmann (sculpted by Paul Granlund)

- Biblical garden featuring date palm, pomegranate, fig and olive trees, caper, mint, citron and other plants mentioned in the Bible

- Ottoman garden with water features and xeriscape

Popular culture

[edit]Douglas Trumbull, the director of the 1972 science fiction classic film Silent Running, stated that the geodesic domes on the spaceship Valley Forge were based on the Missouri Botanical Garden's Climatron dome.[9]

-

Site plan, as of 1974–1977

-

View of Seiwa-en, the largest Japanese garden in North America

-

Eight Bridges (yatsu-hashi) design in the Seiwa-en

-

Henry Shaw's mausoleum at the Missouri Botanical Garden, with a glass art piece by Dale Chihuly in front of it as of 2023

-

Gladney Rose Garden in 2023

-

Swift Family Garden in 2023. The Linnean House is at the right.

-

Fountain in the garden

-

Statue of George Washington Carver

-

Part of the children's area

-

Part of the children's water-play area

-

The Missouri Botanical Garden's Prairie Garden in 2023. It includes stone paths and metal animal silhouettes.

-

English Woodland Garden in 2023

Butterfly House

[edit]Missouri Botanical Garden also operates the Sophia M. Sachs Butterfly House in Chesterfield. The Butterfly House includes an 8,000-square-foot (740 m2) indoor butterfly conservatory as well as an outdoor butterfly garden.

EarthWays Center

[edit]The EarthWays Center is a group at the Missouri Botanical Garden that provides resources on and educates the public about green practices, renewable energy, energy efficiency, and other sustainability matters.[10]

Shaw Nature Reserve

[edit]The Shaw Nature Reserve was started by the Missouri Botanical Garden in 1925 as a place to store plants away from the pollution of the city. The air in St. Louis later cleared up, and the reserve has continued to be open to the public for enjoyment, research, and education ever since. The 2,400-acre (9.7 km2) reserve is located in Gray Summit, Missouri, 35 miles (56 km) away from the city.[11]

The Plant List

[edit]The Plant List is an Internet encyclopedia project to compile a comprehensive list of botanical nomenclature, created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and the Missouri Botanical Garden.[12] The Plant List has 1,040,426 scientific plant names of species rank, of which 298,900 are accepted species names. In addition, the list has 620 plant families and 16,167 plant genera.[13]

Living Earth Collaborative

[edit]In September 2017 the Missouri Botanical Garden teamed up with the St. Louis Zoo and Washington University in St. Louis in a conservation effort known as the Living Earth Collaborative.[14] The collaborative, run by Washington University scientist Jonathan Losos, seeks to promote further understanding of the ways humans can help to preserve the varied natural environments that allow plants, animals and microbes to survive and thrive.[15]

Sponsorship

[edit]Monsanto had donated $10 million to the Missouri Botanical Garden since the 1970s, which named its 1998 plant science facility the Monsanto Center.[16] The center has since been renamed to the Bayer Center following Monsanto's acquisition by Bayer.[17]

Publications

[edit]See also

[edit]- List of botanical gardens and arboretums in the United States

- Peter F. Stevens, a biologist working in the Missouri Botanical Garden

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Missouri

- National Register of Historic Places listings in St. Louis south and west of downtown

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ "Missouri Botanical Garden". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ "Herbarium". Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ "Index Herbariorum". Steere Herbarium, New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places – Nomination Form" (PDF). Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ "MISSOURI BOTANICAL GARDEN BOARD OF TRUSTEES APPOINTS DR. PETER WYSE JACKSON AS SUCCESSOR TO GARDEN PRESIDENT DR. PETER H. RAVEN" (PDF). Mobot.org. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ Neman, Daniel (February 15, 2024). "Three St. Louis-area sites added to Underground Railroad program". STLtoday.com. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "ฝาก 20 รับ 200 ถอนไม่อั้น". Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Commentary accompanying the DVD release of the film Silent Running.

- ^ "Conservation in Action: the EarthWays Center". Missouribotanicalgarden.org. Archived from the original on April 26, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "Shaw Nature Reserve". Shawnature.org. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "Discovery News: World's Largest Plants Database Assembled". News.discovery.com. December 29, 2010. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ CBC: US, British scientists draw up comprehensive list of world's known land plants[dead link]

- ^ Jost, Ashley (September 6, 2017). "Washington U., St. Louis Zoo and Missouri Botanical Garden team up to tackle conservation". stltoday.com. Retrieved August 2, 2019. [verification needed]

- ^ "Our Mission". Living Earth Collaborative. September 1, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2019. [verification needed]

- ^ Press release Missouri Botanical Garden receives $3 million gift from Monsanto Company toward development of a World Flora Online. Missouri Botanical Garden, June 5, 2012

- ^ No official announcements or press, but the difference can be seen on the Garden's website before and after Monsanto acquisition by Bayer (difference in name in caption for second photo); before: https://web.archive.org/web/20130822224927/https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/plant-science/plant-science/resources/herbarium.aspx , after: https://web.archive.org/web/20210604074747/https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/plant-science/plant-science/resources/herbarium.aspx .

External links

[edit]- CS1: unfit URL

- Missouri Botanical Garden

- Botanical gardens in Missouri

- Culture of St. Louis

- 1859 establishments in Missouri

- National Historic Landmarks in Missouri

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in Missouri

- Buildings and structures in St. Louis

- Tourist attractions in St. Louis

- Geography of St. Louis

- Botanical research institutes

- National Register of Historic Places in St. Louis

- Chinese gardens

- Woodland gardens