Sue Ryder

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

The Baroness Ryder of Warsaw | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Margaret Susan Ryder 3 July 1924 Leeds, Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 2 November 2000 (aged 76) Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, England |

| Other names | Margaret Susan Cheshire |

| Known for | Sue Ryder Foundation |

| Title | Baroness Ryder of Warsaw (suo jure) Lady Cheshire |

| Spouse(s) | Leonard Cheshire, Baron Cheshire |

Margaret Susan Cheshire, Baroness Ryder of Warsaw, Baroness Cheshire, CMG, OBE (née Ryder; 3 July 1924 – 2 November 2000), commonly known as Sue Ryder, was a British volunteer with Special Operations Executive in the Second World War, and a member of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, who afterwards established charitable organisations, notably the Sue Ryder Foundation (now known as simply Sue Ryder).

Early life

[edit]Margaret Susan Ryder was born in 1924 in Leeds, the daughter of Charles Foster Ryder and Mabel Elizabeth Sims.[1] The family lived at Scarcroft Grange near Leeds; the house now has a blue plaque, installed by Leeds Civic Trust in 2011.[2] She was educated at Benenden School.

Year of birth

[edit]According to her autobiography, Child of My Love, Ryder was born on 3 July 1923. This was repeated by The Daily Telegraph in her obituary in November 2000, adding that "Lady Ryder of Warsaw, better known as Sue Ryder, has died aged 77", as well as by the BBC and many other news sources.[3]

Her birth and death certificates both put the date one year later, on 3 July 1924,[4] as does a plaque unveiled in honour of Sue Ryder and Leonard Cheshire in St Mary the Virgin's Church, Cavendish in Suffolk. Ryder joined the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry as a volunteer in January 1942. Her personal file is held at FANY HQ in London and mentions both 1923 and 1924 as her birth year.

Second World War service, FANY and SOE

[edit]In January 1942 she joined the ‘Free FANY’, the section of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry which had not been absorbed into the Auxiliary Territorial Service (FANY-ATS) in 1939. Free FANY Special Units were voluntary and independent and as such were used by, amongst others, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Ryder was assigned to the Polish section of the SOE and in 1943 she was posted with the Polish Unit to Tunisia, Algeria and later to Italy.[5] The Poles had been trained by SOE as parachutists to infiltrate Poland. In 1945 she returned to the UK and was attached to the Polish Forces in Scotland. She was discharged in November 1945.

Post-war activities

[edit]After the war, Ryder volunteered to do relief work in Europe, initially with the Amis Volontaires Français, the Red Cross and the Guide International Service.[6] Her association with SOE made initial service in Poland difficult but she persevered, much affected by her time spent with various Polish forces. Official relief organisations had withdrawn by 1952, and Ryder decided to stay on working alone, visiting prisons and hospitals. In the aftermath of war there were many non-Germans, young men in particular, who were unable to return to their own countries either due to lack of documentation or because their families were all dead. As a result, some of these young men turned to crime, usually so they could buy food or in some cases, to take revenge on their former captors. It was these people that Sue Ryder advocated for, calling them her 'Bods'.[7] She drove all over Germany to visit them in prisons, where she was often not welcomed by the authorities. At one time there were 1400 'Bods' in prisons, mainly Polish but also from Albania, Czechoslovakia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. Ryder appealed on their behalf for their sentences to be reduced, or for their release, and for many she would be their only visitor. Some were executed and she would stay to pray with them. Among those who were released, she managed to repatriate some to Britain. Right up until two years before her death in 2000, there were still three prisoners she would visit every December, driving herself across Europe.[8]

Charitable work

[edit]Because of her experiences in SOE and the brave people she met, Ryder was determined to establish a 'living memorial' to the millions of people who had died in world war, and to all those who continued to suffer and die because of persecution. In 1953 she established her charity, initially the Forgotten Allies Trust,[9] which later became the Sue Ryder Foundation.[10] In 1996 her charity became Sue Ryder Care, changing its name to Sue Ryder in 2011.[11]

Ryder established the first Home in Britain at her mother's house in Cavendish, Suffolk in 1953, having already founded the St Christopher Settlement and St. Christopher Kries in Germany.[12] These homes and projects were initially for survivors of Second World War concentration camps. The Cavendish home, also where Sue Ryder and her family lived, continued to provide care for sick and disabled people until 2001.

Until the 1970s, homes were established in Poland and the countries of the former Yugoslavia. The local authorities in each country built the foundations of the homes and installed utilities. Prefabricated buildings and equipment were sent out from the UK and erected by local builders together with UK tradesmen. Over twenty homes in each country were started in this way, and Ryder would make annual visits to look at sites for new homes and see what other help was needed.[13]

Aware of the difficult conditions in which many of the survivors of the concentration camps continued to live in Poland, Ryder began a Holiday Scheme. Initially this started in Denmark, and Ryder would drive individuals there from Poland where they would stay with friends. The scheme transferred to the UK in 1958 and with the home in Cavendish already full, Ryder leased the south wing of nearby Melford Hall.[14] For eleven years, many survivors of the concentration camps stayed for three or four weeks on holiday. Ryder continued to look for a more permanent property, and finally Stagenhoe Park in Hertfordshire became a Sue Ryder Home and continued the Holiday scheme. When the scheme came to an end, the home continued to provide care and is now a neurological care centre.[15] Until the 1990s, Sue Ryder Homes opened in Britain and are run today by the charity Sue Ryder as hospices and neurological care centres, supported by a network of over 400 Sue Ryder shops. At one point, there was even a Sue Ryder shop on the Ascension Islands.[16]

Sue Ryder's international work expanded to include homes and projects, including mobile medical units, in Belgium, the Czech Republic, Israel, Italy, France, Albania, Greece, Ireland, Ethiopia and Malawi and work continues in many of these countries today.[17] In 1958, the year before their marriage, Sue Ryder and Leonard Cheshire established a centre in India called Raphael, near Dehra Dun.[18] The centre included homes for those with leprosy, people with learning disabilities, orphaned and destitute children, a school and a hospital with a tuberculosis wing. Fundraising for this project started in Australia and New Zealand, and both projects continue today.[19] The work at Raphael became their joint charity Ryder-Cheshire, which continues in the UK as Enrych,[20] supporting people with disabilities by providing access to leisure and learning opportunities through volunteers.[21] In Australia, Ryder-Cheshire Australia continues to support Raphael in India, a home at Klibur Domin in Timor-Leste and two Australian Homes in Mt. Gambier and Melbourne.[22] Raphael is a separate trust and is the State Nodal Agency Centre (SNAC) Uttarakhand for persons with autism, cerebral palsy, learning disabilities and multiple disabilities.[23]

In 1995, the High Anglican Christian Community of St Katharine of Alexandria gave the house and grounds at Parmoor, now known as St Katharine’s, to Sue Ryder. She made the house into the headquarters of her independent charity, the Sue Ryder Prayer Fellowship, which she founded in 1984.[24] The Fellowship was conceived by Lady Ryder to be a “powerhouse of prayer” for the needs of others, and especially for the work carried out across the world in the name of Sue Ryder. The house is a Christian house of prayer, and welcomes people from all denominations and none and all walks of life, in a spirit of ecumenism and reconciliation.[25]

In 1998, Sue Ryder retired as a trustee and severed her links with Sue Ryder following a dispute with the other trustees, whom she accused of betraying her guiding principles.[26]

In February 2000, Ryder set up the Lady Ryder of Warsaw Memorial Trust (previously called the Bouverie Foundation)[27] to continue charitable work according to her ideals. The Trust is devoted to the relief of suffering and seeks to render personal service to those in need, regardless of age, race or creed, as part of the Human Family.[28] As of 2021, it started working with Bristol and Newcastle Universities to help train more doctors.[29]

Awards and honours

[edit]Sue Ryder was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1957.[30]

Together with her husband Leonard Cheshire, she received a joint Variety Club Humanitarian Award in 1975, presented by HRH Princess Margaret.[31]

Ryder was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in 1976.[32]

House of Lords

[edit]Ryder was made a life peer on 31 January 1979, being created Baroness Ryder of Warsaw, of Warsaw in Poland and of Cavendish in the County of Suffolk.[33][34] In the House of Lords, Ryder was involved in debates about defence, drug abuse, housing, medical services, unemployment, prison reform and race relations.

Ryder continued to speak for Poland and when the Communist rule there collapsed, she arranged lorries of medical and food aid. In 1989 Ryder made an appeal through The Daily Telegraph to obtain more funding and collected £40,000 through the Lady Ryder of Warsaw Appeals Fund.[35]

In a Lords debate for what became the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, Ryder moved an amendment on behalf of Lord Ashbourne (who was absent) proposing a 'Restriction on custody of children by homosexuals'. Ashbourne's amendment proposed to make it a criminal offence for "any homosexual man or woman, other than the natural parent, to have the care or custody of a child under the age of eighteen."[36] Ryder withdrew the amendment when it received limited support from peers, stating: "My Lords, I am indeed grateful to noble Lords who took part in the debate on this amendment, which tries to safeguard children and is not intended as an attack on those with homosexual tendencies".[37]

Her husband was made a life peer in 1991, as Baron Cheshire, as a result of which Ryder obtained the additional title Baroness Cheshire.

Death

[edit]Ryder died in Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, on 2 November 2000, aged 76.[38]

Works

[edit]Ryder wrote two autobiographies:

- And the Morrow is Theirs (1975)

- Child of My Love (1986)

Biographies:

- A.J. Forest, But Some There Be. London: (Badger Book), 1959.

- Tessa West, Lady Sue Ryder of Warsaw: Single-minded philanthropist. Chicago: Shepheard-Walwyn, 2019.

- Joanne Bogle, A Life Lived for Others Leominster: Gracewing, 2022.

Podcast:

For what would have been her centenary year in 2024, the Lady Ryder of Warsaw Memorial Trust produced a podcast 'Never Standing Still: Retelling the story of Sue Ryder' on Spotify.

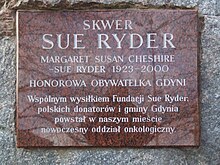

Museum

[edit]Ryder set up the Sue Ryder Museum at Cavendish to tell the story of her work and promote the causes of those she helped. This museum was closed upon the sale of the Cavendish Sue Ryder home in 2001. The exhibits from the museum were handed to the Fundacja Sue Ryder (her Polish foundation) and in 2010, the city of Warsaw kindly lent to the Foundation one of two pavilions of the Mokotów Tollhouses at 2 Union of Lublin Square in Warsaw, to house the new museum. It was opened 19 October 2016.[39]

The Sue Ryder home at Cavendish was purchased by another care provider and renamed Devonshire House.[40] A remembrance room to Lady Ryder and the residents of the Cavendish home was set up in 2019 and opened by her children Jeromy and Elizabeth Cheshire on 18 February 2019.[41]

References

[edit]- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ Open Plaques. "Lady Ryder of Warsaw". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Lady Ryder of Warsaw". The Telegraph. 3 November 2000. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "England & Wales Deaths 1837-2007". District: Bury St. Edumunds 7421A. Register No. A26D. Entry 001. ONS. November 2000.

- ^ "Ryder, Sue (oral history)". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ Ryder, Sue (1997). Child of My Love. London: Harvill. p. 176.

- ^ Hinkson, Pamela (3 November 2000). "Baroness Ryder of Warsaw". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ Ryder, Sue (1997). Child of My Love. London: Harvill. p. 176.

- ^ Ryder, Sue (1997). Child of My Love. Harvill. pp. 225–226.

- ^ "Sue Ryder Foundation". Charity Commission for England and Wales. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Sue Ryder". Charity Commission for England and Wales. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Cheshire Smile (1961). "Forgotten Allies Trust". Cheshire Smile. 7 (1): 22–23. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Ryder, Sue (1997). Child of My Love. London: Harvill. pp. 387–388, 422–423.

- ^ Ryder, Sue (1997). Child of My Love. London: Harvill. pp. 453–454.

- ^ Sue Ryder. "Sue Ryder Neurological Care Centre Stagenhoe". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Sue Ryder. "Shop with us". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Lady Ryder of Warsaw Memorial Trust. "Sue Ryder 'Family of Foundations'". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Raphael Ryder Cheshire. "Our Story". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Ryder Cheshire Australia. "RCA History". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Enrych". Charity Commission for England and Wales. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Enrych. "About Enrych". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "About Us". Ryder-Cheshire Australia. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Raphael Ryder Cheshire. "About the organisation". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "The Community of the Sue Ryder Prayer Fellowship". Charity Commission for England and Wales. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ St Katherine's Parmoor. "The Sue Ryder Prayer Fellowship". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Charity founder Baroness Ryder dies", BBC News, 2 November 2000.

- ^ "The Lady Ryder of Warsaw Memorial Trust". Charity Commission for England and Wales. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Lady Ryder of Warsaw Memorial Trust. "Home". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Lady Ryder of Warsaw Memorial Trust. "Medical Scholarship". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "No. 41089". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 June 1957. p. 3381.

- ^ Cheshire Smile (1977). "Extracts from the report of the Trustees". Cheshire Smile. 21 (4): 5. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "No. 46919". The London Gazette (Supplement). 12 June 1976. p. 8017.

- ^ "No. 47761". The London Gazette. 2 February 1979. p. 1497.

- ^ "No. 47908". The London Gazette. 19 July 1979. p. 9066.

- ^ "Lady Ryder of Warsaw". The Daily Telegraph. 3 November 2000. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Johnson, P. & Vanderbeck, R.M. (2014). Law, Religion and Homosexuality. Routledge.

- ^ Hansard (12 July 1994). Criminal Justice And Public Order Bill. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Hinkson, Pamela (3 November 2000). "Obituary Baroness Ryder of Warsaw". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Wisniowska, Kasia (11 March 2018). "Discover a story of the greatest volunteer Sue Ryder in her Warsaw museum". Museeum. Archived from the original on 19 June 2019. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Anchor. "Devonshire House Sudbury". Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Malina, Thomas (18 February 2019). "Devonshire House care facility in Cavendish dedicates room in memory of philanthropist Sue Ryder". Suffolk News. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

External links

[edit]- 1924 births

- 2000 deaths

- People educated at Benenden School

- British philanthropists

- British baronesses

- Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Converts to Roman Catholicism

- Crossbench life peers

- Life peeresses created by Elizabeth II

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- People from Leeds

- People from Bury St Edmunds

- British Special Operations Executive personnel

- Women in World War II

- Founders of charities

- 20th-century British women politicians

- Leeds Blue Plaques

- Spouses of life peers

- Military personnel from Leeds

- Guide International Service volunteer